While 'studiositas' is a strength of mind, the mind infected by the often-misunderstood vice of 'curiositas' is in one way or another blinded to the truth of real things.

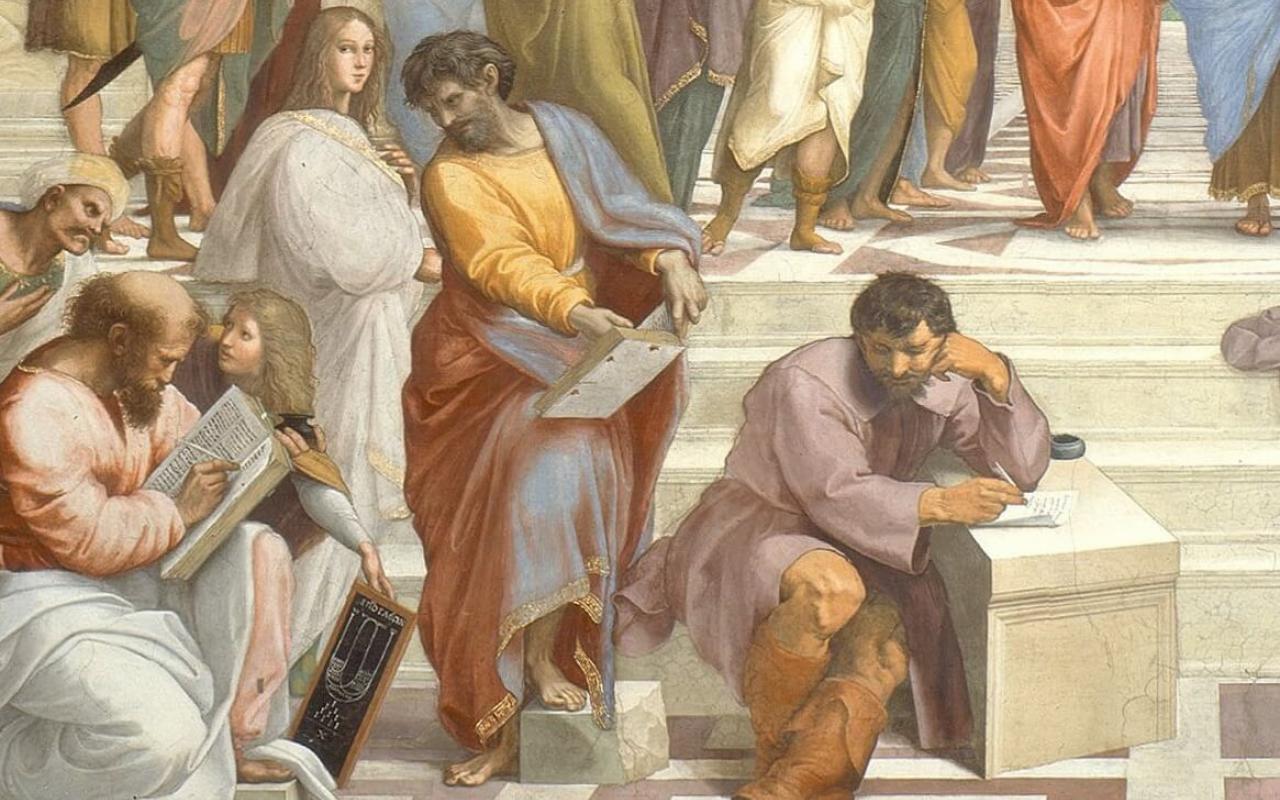

“All men by nature desire to know” (Aristotle, Metaphysics).

“Put off your old nature which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful lusts, and be renewed in the spirit of your minds” (Ephesians 4:22-23).

These two Latin words, studiositas and curiositas, have a long and important history in the Christian understanding of the life of the mind. Unfortunately, when they are transliterated into English by the words “studiousness” and “curiosity,” they significantly change their meaning and we can lose much of their significance. The tradition has understood studiositas as a quality belonging to a strong mind, and curiositas as a vice of a weak one. Let’s see if we can unpack their meanings toward a better understanding of this virtue and this vice as a way of sharpening and strengthening our minds.

The Virtues

According to long Christian usage, a virtue is a habitual quality of strength attaching to one of our human faculties. Our most important faculties, those that represent the image of God in us, are our minds and our wills. Intellectual virtues are strengths of mind, and moral virtues are strengths of will. A given virtue is a kind of balance, a “golden mean” that holds our faculties steady and upright and keeps them from tumbling into weakness, whether by diminishing or by exaggerating a given virtue. It is therefore common when describing a virtue to note its excess and its defect. For example, the moral virtue of courage is a habitual strength of the will that enables its possessor to be ready to suffer for a good cause. Excess of this strength is foolhardiness; its defect is cowardice.

In Thomas Aquinas’s classic treatment of the virtues, the virtue of studiositas is discussed under the broader category of temperance (Summa IIaa, 166-7). Temperance comes into play to strengthen and balance our natural powers and desires. We have a natural appetite for food, but that appetite needs to be properly tempered such that we eat sensible amounts of the right kinds of food. Otherwise what was meant as something good can become harmful and destructive. The same principle holds true with our natural appetite for sexual union. God created us with these appetites, and in themselves they are beneficial to us. But as a result of humanity’s fallen nature they tend to become inflamed and to turn on their possessors. Hence the need to cultivate virtues with God’s help that will master our natural powers and guide them by what is reasonable and loving.

Studiositas

As Aristotle said a long time ago, we all have a natural desire to know. No one has to teach us this desire. An infant comes out of the womb eagerly learning whatever it can. The mind is made by God for truth and naturally rushes toward it. The ultimate goal of our minds is to perceive Truth Himself, the ultimate truth, and in that possession to become fully happy. When we use our minds well, we are giving glory to God and becoming more truly and fully human. But as with our physical desires, our desire for knowledge needs to be rightly tempered. Our minds are our most God-like faculty, and in keeping with the maxim that “the corruption of the best is the worst,” it follows that the corruption of the mind leads to the most serious perversions of our human nature. Studiositas is the virtue that maintains our intellects in proper balance such that we can firmly and confidently grasp the truth of things.

This is where the English word “studiousness” fails as a description of this virtue. The need to be studious mainly applies to full-time students, and refers to the practice of “hitting the books,” of being conscientious in getting our assignments done. This is certainly an important habit for a student, but it hardly touches the rich depths of the virtue of studiositas. The strength of mind cultivated by this virtue goes far beyond student life. It is necessary for every one of us, all the time. Whatever our age, occupation, or circumstances, our minds are constantly reaching out toward knowledge. If our desire for gaining knowledge is not rightly ordered, we will tend to wander into distortions of the truth, misunderstand the most important aspects of reality, and possibly lose our souls. Our intellectual faculties need tempering even more than our physical ones, since they are stronger and more constantly in use.

There have been times and places in the Church’s history when rousing the intellect was the task at hand. But we live in an age of intense curiositas, one in which we are constantly being led to feed our desire for knowledge in ways that dull its capacities and darken its vision.

To understand the habit of studiositas it helps to look at what happens when our desire for knowledge gets out of balance, whether by excess or defect. The two vices associated with this virtue of strength of mind are negligence, its defect, and, in its Latin form, curiositas, its excess. Each is worth examining, but the second is especially important to consider, since we are living in an age of rampant curiositas.

Negligence

Negligence refers here to the tendency to avoid the mental work necessary to grasp knowledge. Many of its expressions are obvious and hardly need detailing. Our desire for physical comfort can often blunt the keenness of mind necessary to understand some aspect of reality, and we can be smitten by a mental lethargy that prefers to “zone out” rather than to engage important truths. More momentously, we often purposely avoid gaining knowledge of truths that will prove inconvenient or challenging to us, and we can turn our minds away from whatever makes us uncomfortable. The most important questions facing every human have to do with our destiny, our reason for being alive, our moral state, questions that turn on God’s existence and our duties toward him. There are many people who have no firm view on any of these questions, not because they have expended energy on them and have found the results inconclusive, but because they have never shaken off their sleepiness of mind and roused themselves to seriously consider them. They are content to leave such questions not only unanswered, but unasked. This state of intellectual torpor is made perilously easy for us by the constant flood of mindless electronic entertainment that constantly surrounds and entices us.

Curiositas

Negligence of mind, the blunting of our natural desire to know, is a common enough fault and we all deal with it at times. But the appetite for knowledge is so strong in us that we face a far more formidable temptation coming from the opposite direction. We mainly fail in the virtue of studiositas by excess: we desire knowledge too greedily; we fall into the weakness of mind called curiositas. One can see that the English word “curiosity” is misleading as a description of this vice. Curiosity typically describes the natural human desire for knowledge. A lack of curiosity in this sense would be as unhealthy to a human mind as a lack of appetite for food would be for a human body. Curiositas on the other hand is always a corruption of the mind’s purpose, which is to grasp the truth in its fulness. The mind infected by curiositas is in one way or another blinded to the truth of real things.

At this point someone might make the objection: “Knowledge is in itself good, and the desire to know is a God-given human faculty. How can we desire too much knowledge? Surely this is a case of the more the better. Provided we are gaining real knowledge and not lies or falsehood, where’s the problem?” The answer to this objection touches on the complex nature of reality, and on the convoluted state of fallen humans. Knowledge is of itself good, and the desire to know is indeed a God-given quality. But due to our damaged intellects there are many roads by which our untempered desire for knowledge can lead us astray, and in pursuing knowledge wrongly we can paradoxically be left with a weaker understanding of things. What follows are six expressions of curiositas, each of which dims our vision of what is true and good.

1. Seeking knowledge of one aspect of reality while neglecting the wider picture.

Truth is an integrated whole, and a firm grasp of the truth demands that we understand the hierarchy of truths and the way that various aspects of reality impinge upon each other. The habit of studiositas keeps the whole of things in view when seeking knowledge of some part of the whole. Curiositas can inflame and distract the mind by engrossing it in one facet of things to the exclusion of all else. It is often said, “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” The person who masters only one aspect of things or who gains only a shallow understanding of something, often thinks that he knows more than he does, and can blunder about causing serious damage. We live in an age of the expert, and our whole educational system is skewed toward knowing a great deal about a very small slice of reality. We are taught to become masters of technical detail to the exclusion of the most important matters. The result of this kind of curiositas can be seriously troubling. The economist who knows only how to manipulate stocks and whose machinations lead to economic failure and widespread suffering; the biochemist who delves into the secrets of genetics but who knows nothing of the ethical implications of the research; the computer engineer who devises clever but addictive games and apps without considering their psychological and social results; the politician who is expert at electioneering and public relations but who knows next to nothing about what is needed for a stable social order; these and many other similar examples of curiositas constitute one of the plagues of our time.

2. Avidly pursuing unimportant knowledge rather than knowledge that will allow us to fulfill our obligations.

It is easy for our minds to become enchanted with the knowledge of something pleasurable or interesting, like following sports, or practicing gardening, or learning a special skill, and to allow our pursuit of it to overly dominate our minds. When that happens, knowledge of what should demand our intelligent attention, like raising our children, performing our work well, or keeping abreast of our finances, can be given short shrift. We can neglect our duties because of our rampant desire to know everything about some trivial matter. Yet more significantly, there are many Christians who are highly skilled in business, law, medicine, or technology, but who have a fifth grader’s understanding of the mysteries of their faith. If they knew as little about their work as they did about their immortal souls they would be laughed out of their jobs. Studiositas keeps the proper hierarchy of knowledge in view, and apportions the right amount of time and energy to what is important and what is less important.

3. Seeking knowledge about things we have no right to know or trying to gain knowledge by unlawful means.

We all know this form of curiositas. It is so rampant around us that it becomes difficult not to grow dull to it. Curiositas is often an expression of pride. The fallen human mind resents the idea that there is anything that is off-limits to know. It wants to assume the place that belongs only to God. God created everything, he knows everything concerning his creation, and he has an intrinsic right to that knowledge. He is the source of all knowledge. We, his creatures, are not the origin of knowledge and we do not have the right to know everything. When it comes to dealing with our fellow humans, the proper dignity of others demands that we place limits on our desire for knowledge. Yet the temptation to the pride of curiositas is ever-present. We feed on the inner secrets of other people; we greedily devour tidbits of intimate information that have nothing to do with us; we revel in watching the emotional state of people in crisis. The bad habit of gossip is an indulgence in this kind of curiositas. So is the blinding practice of looking at pornography. The majority of what passes for “news,” whether on TV news stations, social media, or printed newspapers, falls under this kind of unlawful knowledge. We love especially to hear of other peoples’ sins and failures, since it allows us to look down on them. The virtue of studiositas applies a healthy asceticism to this overweening desire. Where personal knowledge of others does not fall under our duty, as with parents, teachers, and pastors, or involves giving aid to others, as with medical practitioners and counselors, the healthy and balanced mind will turn away from this corrupting desire, knowing that it will enervate and sully the spirit and make it difficult to see the reality of other immortal souls in their proper proportions.

4. Seeking knowledge in order to gain power over others.

The Englishman Francis Bacon famously wrote that “knowledge is power.” Some two hundred years later, in line with Bacon’s thought, the philosopher Immanuel Kant coined what he claimed was the motto for the whole of the Enlightenment: Sapere aude!: Dare to know! Don’t be afraid to seize upon whatever knowledge will make humans more powerful. Bacon and Kant no doubt naively hoped that such knowledge would be sought after and used mainly for the betterment of humanity. But the last few hundred years have taught the lesson that knowledge can be eagerly sought for the worst of reasons. We can pursue knowledge of weaponry that will allow us to kill people in ever greater numbers; we can investigate human psychology and anatomy for the purposes of manipulation and torture; we can develop information technology to dominate human behavior and amass personal wealth. The virtue of studiositas quells the lust for this kind of knowledge by keeping in view the ultimate goal of the gift of our minds, truth and goodness as found in God.

5. Seeking knowledge in order to take pride in our intelligence and show ourselves superior to others.

Everyone is annoyed by the “know-it-all.” While we are usually grateful to find someone who can inform us of important facts or who can give us wisdom when we genuinely need it, the person who is constantly and egotistically spouting off becomes obnoxious. Yet we are all prone to this often subtle kind of curiositas. We want to have the latest information on whatever is being discussed; we want to be a member of the inner circle “in the know” concerning what is happening around us; in general we want to be consulted and paid attention to. Surveys have shown that the quality people most desire, even more than being thought physically attractive, is to be thought intelligent. Curiositas seizes upon this desire and runs with it in the direction of self-promotion.

6. Seeking knowledge of created things for their own sake without viewing them in relation to the source and center of all things, God.

This gets to the heart of the matter, and helps make clear why curiositas is always a diminishment of true sight, even when the knowledge gained is genuine knowledge. Humans are not merely informational units, organisms with wetware bodies housing the software of our brains. We are immortal beings, enfleshed souls destined to share the life of God. Because God is both absolute truth and absolute goodness, all human knowing has a moral aspect. If God, the center of all reality, is left out of view or is given a distorted place in our picture of things, the whole vision of ourselves, others, and the world becomes blurred, even if some of the details are accurately seen. God is light, the one in whose presence we can see. Where there is no light, there can be no seeing. When our vision of truth is corrupted by the absence of God, we lose our grip not only on truth, but also on goodness, and unforeseen evils sprout up in the midst of our activity. The horrific experiments of the last century witness to the human suffering that this kind of rampant curiositas can cause. Both Soviet communism and Nazi fascism prided themselves on being scientific and enlightened. Yet for all their knowledge they were miserable failures with a staggering human cost, because they insisted on leaving God, reality himself, out of their humanly constructed plans.

God created us to know, to use our minds with all the energy and thoughtfulness we can bring to bear. If we were living in an age of intellectual negligence, cultivating the virtue of studiositas would mainly involve rousing ourselves and others to a proper appreciation of the powers and possibilities of the mind. There have been times and places in the Church’s history when rousing the intellect was the task at hand. But we live in an age of intense curiositas, one in which we are constantly being led to feed our desire for knowledge in ways that dull its capacities and darken its vision. In order to redress the virtuous balance, we will need to practice an asceticism of the intellect, training our minds to grasp the heart of reality in its true proportions and restraining ourselves from reaching out toward knowledge that will only distract and may ultimately destroy us. By keeping God in the center of things where he belongs, the practice of studiositas will be a great help to us and to those around us as we seek the clarity of true sight.