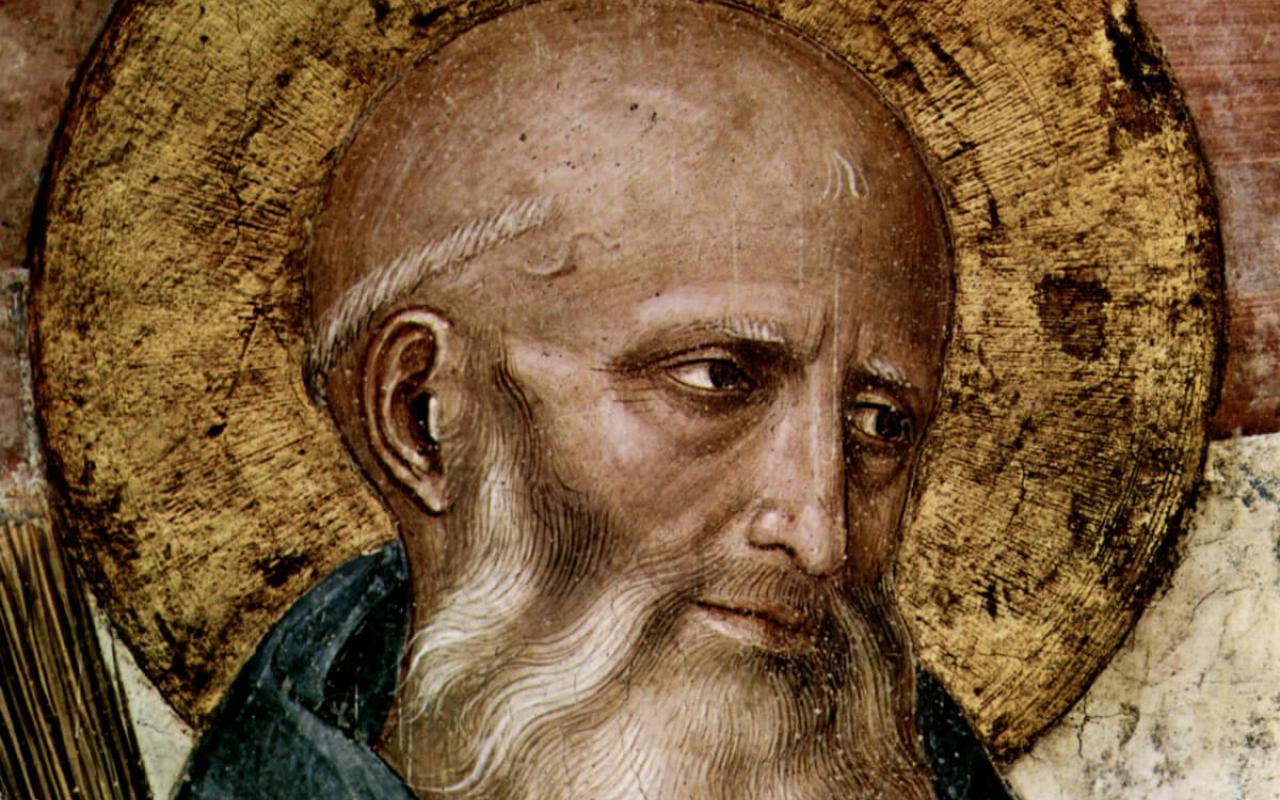

Saint Benedict taught us that the key to living a rich, full, and useful human life is to keep our eyes fixed on the things of God.

Saint Benedict (AD 480-547) is a patron saint of students, as well as one of the patron saints of Europe. He has had an immense influence on our educational practice, and he had much to do with the shape of Western culture. Yet when St. Benedict founded the monastery of Monte Cassino in AD 529, what we would call 'education' was not primarily on his mind, and he was certainly not thinking about European civilization.

Benedict was an educated young man from a well-to-do family in central Italy. He had received the kind of classical education available to such a youth at a time when the impressive Graeco-Roman educational tradition was still available, although in a weakened state. Despite the advantages such an education gave him for making his prosperous way in society, however, Benedict ran away from the life laid out for him. While still a young man he embraced the calling of a hermit, living for three years in a cave at Subiaco, spending his time in prayer and fasting and flight from the world. As his reputation for sanctity grew, he became involved in helping groups of monks order their lives together, eventually founding his famous monastery.

Benedict’s greatest contribution to the Church and to western civilization was a short book that he wrote, his Rule, the most influential document of its kind in history. Benedict’s monastic rule of life performed the remarkable feat of maintaining the zealous focus of early monasticism within a spirit of moderation and human balance. His ideal became so significant to the emerging culture that Benedict has often been called “the father of western civilization.” For a thousand years, the houses founded upon his vision of the Christian life were the spiritual and cultural heart of Europe, and many continue to follow his rule today.

Benedict and his tradition have schooled the whole of our civilization in an essential lesson, one that our current society would do well to re-learn. He taught us that the key to living a rich, full, and useful human life is to keep our eyes fixed on the things of God.

The men and women who first gathered together under Benedict’s rule as monks and nuns in monasteries and convents were not pursuing an explicitly educational purpose. Their goal was rather to live the Christian life with as much intensity as they could muster, spending their time in work and in worship, turning away from the allurements of the world, and praying for their fellow Christians and fellow humans as they awaited the coming of Christ in the New Jerusalem. Benedict taught his followers that their vocation involved turning away from the normal life of the society in order to seek personal holiness and to pray on its behalf.

This raises an interesting question: If education was not Benedict’s main objective, how did he come to be counted as one of the greatest educators of all time? How was it, furthermore, that someone whose explicit purpose was to turn away the world came to be among those most honored as one of its greatest benefactors?

To understand this seeming contradiction is to perceive the necessary connection between the life of Christian discipleship and the growth of a genuinely human culture. It is to see that although Benedict’s educational significance was unintended, it was not in the least accidental. Those who make the pursuit of Christ their primary aim will find that, unlooked for, human excellence has been achieved along the way. Jesus had himself predicted this: “Seek first the kingdom, and all these other things will be added as well” (Matthew 6:33).

Benedict’s Rule calls the monastery a “school for the service of Christ.” By 'school,' Benedict did not mean what we usually think of by that term, namely, an organized place of classes and book learning. He meant rather a place of training in discipleship. Nevertheless, Christian discipleship demands a close acquaintance with the life and teaching of the Master, Christ. St. Jerome had already taught the ancient world that “ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ.” The monks spent many hours each day in prayer and study, which meant reciting the Psalms together and engaging in what they called lectio divina, a prayerful reading of the sacred text. This meant, at the very least, that the monks needed to know how to read and that the monastery had to own some books: the Scriptures and liturgical texts for the Mass, and along with them some works of the ancient masters for teaching the art of grammar.

Those who make the pursuit of Christ their primary aim will find that, unlooked for, human excellence has been achieved along the way.

Since books were necessary in these self-sufficient societies, the copying of books necessarily became part of a monastery’s activity. Writings in the ancient world were largely committed to papyrus scrolls. Unless very carefully stored, papyrus has a limited shelf life, after which it decays. If books were to be used in the monasteries, they needed after a certain point to be re-copied. As a result, the skills of writing, of preparing parchment and vellum, and of bookbinding established themselves as monastic arts.

Beyond the necessity of reading and writing and copying, the monks needed to practice all the arts of human labor. As self-sustaining economic communities, monasteries grew their own food, raised their own livestock, built their own churches and habitations, and brewed their own beer. As these organized groups of men and women, disciplined and unified by their common spiritual ideals, brought their creative energy to bear on whatever they were doing, by a kind of (super)natural process monasteries emerged as leaders in the society, not only in prayer and liturgy but also in the development of agriculture and animal husbandry, of architecture and music and art, of medical practice and the care of the sick, of administrative and accounting techniques; in short, of all that makes for a healthy and integrated human life.

As time went on, the monasteries founded upon Benedict’s rule became islands of ordered human life, oases of civilization around which many members of the wider society gathered. Not surprisingly, this abundance of cultural wealth in the monastery spilled over into activities and institutions that were explicitly educational. Benedictine libraries became the treasure houses of ancient learning from which all the society’s scholars drew their materials. Monasteries established schools for the laity that came to play a significant role in the development of the medieval university. Many noted scholars were counted among their number, including such great lights as Pope Gregory the Great, the Venerable Bede, Anselm of Canterbury, Hildegard of Bingen, Bernard of Clairvaux, and Prosper Guéranger. Down to our own time, the sons and daughters of Benedict have continued to make important contributions to the education of the Church and the world.

The greatest of the educational accomplishments of the Benedictines has been expressed in a wider field than what we usually call 'education.' Benedict and his tradition have schooled the whole of our civilization in an essential lesson, one that our current society would do well to re-learn. He taught us that the key to living a rich, full, and useful human life is to keep our eyes fixed on the things of God. When we keep first things first, second things will come into proper order. Pope Benedict XVI put it succinctly when speaking about St. Benedict to a group of educational and cultural leaders in France: “Quaerere Deum – to seek God and to let oneself be found by him – that is today no less necessary than in former times. What gave Europe’s culture its foundation – the search for God and the readiness to listen to him – remains today the basis of any genuine culture.”

Further Reading

- The Rule of Saint Benedict

- St. John Henry Newman, Rise and Progress of Universities and Benedictine Essays

- Jean LeClercq, OSB, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God