There is a strange quote scribbled in the margin of my Cicero text (First Oration Against Catiline):

“quae non sunt simulo; quae sunt, ea dissimulantur.”

(“I pretend the things which are not; the things that are, they are hidden.”)

If I had the time to tell them, I would say that the quote represents for me the blindness of the modern world and the triumph of the Cross. I would explain that the modern, Western world believes in itself; that it attributes its successes to its own genius. It pretends to be, as Cicero claimed for himself, homo per se cognitus (a self-made man), often having no gratitude for those who came before. It judges its ancestors––from whom it inherited many things both practical and beyond value––more viciously than ever itself. I would tell the students that the world's utter blindness stems from the fact that it cannot distinguish the real roots of its inheritance. I would share a story from when I lived in Germany and someone told me, “We have a saying in Germany, ‘cast not your pearls before the swine’ or, ‘love your neighbor as yourself.’” It was actually thought by some that these sayings were of Germanic, not biblical, origin! To anyone with the least bit of biblical knowledge, this sort of cultural amnesia is staggering. These Germans were giving credit to themselves for the words of God-Incarnate. “Real things are hidden,” I would say to my students, “the Cross and the message of Jesus are obscured in the secular West because they have been assimilated so thoroughly by Western culture.” The roots of our modern world, even some of its most secular manifestations, are Christian.

To illustrate this, I would point to the fact that we moderns do not celebrate the person who climbs the seven summits of Mount Everest the fastest. We celebrate the one-legged person who slowly climbs just one of them. A politician in our world could never win popular opinion by accusing his opponent of identifying with the dregs of society, an accusation Cicero made even more sharply by saying that Catiline was a friend of slaves. Anyone attempting such a thing today would be immediately canceled. Something similar is done each time a television advertisement features a teenage girl making her parents proud by participating in a high school football game, or when a one-armed basketball player scores on an opponent. The underdogs, the victims, and the outcasts are always lionized in our society.

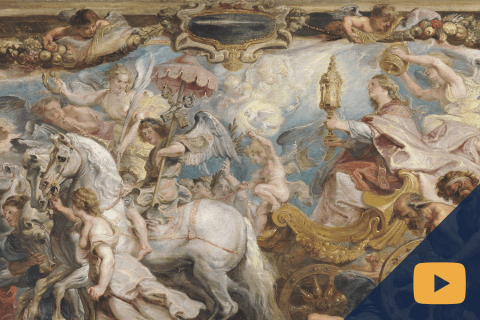

The classical world never produced such propaganda. Theirs was all for the strongest, the victors, the elite talent. To be sure, it was a propagation of conquerors, never the conquered. Simply compare the pre-Christian Dying Gaul statue to the Christ Crucified painting of Velázquez. The first invites the viewer to celebrate a young man completely alone at the throes of death. His Celtic hairstyle, the mustache, and the torc around his neck are there to inform the members of an empire that this man, a foreigner, is worthy of death. The perspective is that of the killers themselves watching the muscular figure die and, in the place of sympathy, there is only pride for destroying such a formidable enemy. The second features Christ on the Cross against a black background. Absent of any narrative scene, one encounters only the bloodied body of Jesus. Rather than pride, this painting evokes intense sympathy for the innocent victim. The Christ Crucified painting was born in the culture of the victim, the Dying Gaul, by contrast, was made for the victors. But for people living in the culture of the victim, such as we are, even the Dying Gaul evokes the sympathy that was never felt by men of antiquity.

Now which of the two works would be acceptable in our society today? If we put modern clothes on it, can you even imagine that we would mainstream a Dying Afghani, or Dying Russian, or even a Dying Terrorist statue? But if we champion a victim, such as happened in 2015 when Westerners agreed to open their borders based on a photo of a two-year-old Syrian refugee who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea, there is no pride, only sympathy––sympathy that seems to many to require action. Doubtless there were probably some, like the Germans with cultural amnesia, saying to themselves, “Well as our saying goes, ‘do to others what you would have them do to yourself’...bring them in.” If such a thing happened in the ancient world, would there be any outpouring of sympathy? Absolutely not. Any man from that time would be as disgusted with the actions of us moderns as Nietzsche was when he said, “Christianity has taken the part of all the weak, the low, the botched; it has made an ideal out of antagonism to all the self-preservative instincts of sound life...” Christianity, as Nietzsche saw, is culturally destructive in that it has taken the part of the weak, and this mad philosopher sought to restore the pre-Christian callousness towards victims. He at least recognized the Christian origins of taking the side of the victim, the low, the botched––sadly, though, he sided with the victors.

To many, it may be a surprise to learn that concern for victims stems from the biblical proclamation that the first shall be last, the least the greatest, and many such passages. St. Paul identifies with the scum of the earth and considers himself among the dregs of all things. He was a preacher to the wise and the unwise, to the Greeks and the barbarians (like the Dying Gaul). He became all things to all people so that he might save some. Never had such an all-encompassing mission, which came from the highest and stooped down to the lowest, been attempted or even conceived. The parable of The Good Samaritan, the moral of which is so obvious to people of today, would have been incomprehensible to a pagan such as Cicero. The much-celebrated and much-envied victim status of today is, at its base, of Christian origin. And yet, currently, there is almost no awareness of this fact. Most in our world are like those listeners of Jesus who had no ears to hear, no eyes to see the real things. We live in the culture of the true victim, Christ Crucified, and this is largely hidden.

Even so, the good news is that there are some equipped with eyes to see the things that are hidden, and they are giving credit to the true roots of the modern world and its concern for victims. Perhaps the most striking case is made by Tom Holland in his masterful book, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. Here he says:

Finally, I'd tell the students that while we uphold the truths of the first shall be last, we shouldn't be so naive as to think that some perversion of this truth couldn't be twisted and used against us. The modern, politically-driven concern for victims, decoupled as it is from the Church, has embedded within itself the proclivity to make new victims. Nothing like this has ever been seen in any place or time in history. In this situation, we should be bold in telling the truth about the modern world and, concerning those who unconsciously usurp the truth and use it for their own ends, we should share in Christ's words, “Father forgive them, they know not what they do.”