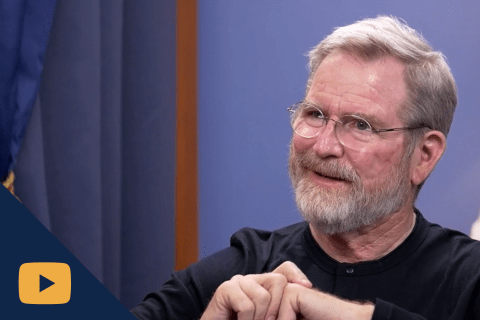

The following homily was delivered by Msgr. James P. Shea in honor of the canonization of St. John Henry Newman on 16 October 2019 at Our Lady of the Annunciation Chapel at the University of Mary in Bismarck, ND.

In a response of joy to the canonization of St. John Henry Newman this past Sunday, we celebrate a Votive Mass for the Evangelization of Peoples. In his honor, I want to offer some thoughts this morning about Christians at a University.

In the readings at Mass these past days, Jesus has been confronting the Pharisees, who emerge in the Gospels as his primary antagonists. When the Divine Son of God became incarnate and faced the powers of evil, he did so for all times and places. The enemies he confronted then, he confronts still, and we, his disciples, confront them as well, both internal to ourselves and in the world around us.

We find that Jesus’ most obstinate enemies, and those upon whom he pronounces the most severe judgment, are the Pharisees. The Pharisees are not easy for us to understand. The nature of their opposition to Christ can easily be missed. There are many false notions about who they were and why Jesus was so displeased with them. Here are a few:

- They were a strange group of men with long beards and odd clothing, impossible to understand unless you study ancient Hebrew society; therefore, they were a historical oddity irrelevant to us, unless you’re into that sort of thing.

- They were religious fanatics who in general took everything way too seriously and in particular were strangely hyper about obeying the law of Moses: they were the awful sort of people who insist on specific devotional customs and who get finicky and fussy about proper liturgical and pious practices. Jesus had to “loosen them up.”

- They were hypocrites, by which is meant that they were liars and deceivers: they were pretending to be what they knew very well they were not. They were a sham.

- They were just a nasty sort of people – angry and vindictive and uncharitable and unreasonable – and they disliked Jesus because he was such a good guy.

The problem which each of these views, apart from the fact that they are false, is that they leave each of us innocent. None of us are any of these obviously unpleasant things, which means that none of us would have been among the primary enemies of Jesus. (We can usually find ways that people we do not like are similar to Pharisees.) This is a serious spiritual misreading of the Gospel. If we cannot find a good bit of the Pharisee in ourselves, as well as in our world, and if we cannot see why the Pharisees were the main opponents of Christ and why we might well have joined them, then we have dodged an important opportunity at self-knowledge and have skillfully sidestepped an important lesson the Scriptures are trying to teach us.

Who then were the Pharisees? What kind of people, in general, were they? Among other things, they were:

- highly educated;

- serious-minded about life;

- strong believers in God and in the importance of religious duty;

- familiar with the Scriptures;

- generally morally upright;

- oriented to a shared life in common with other believers;

- ready to act on their beliefs (many of the early Pharisees had died for their convictions);

- and therefore, not surprisingly, highly respected by the people of their time.

Remember the boast of Paul in Acts 26, when he speaks of having been a Pharisee as something praiseworthy. And it must have been! What sort of life would have attracted a man such as Saint Paul if not one of high seriousness and zealous faith? From many points of view, the Pharisees were the best that the Jewish people had to offer. Yet Jesus was in constant conflict with them. Throughout his ministry, his main fight is not with atheists, nor with obviously immoral people. These would be almost too obvious opponents of the faith he was teaching. Rather, he is consistently opposed by some of the best among his hearers, the most morally earnest and religiously engaged. Why?

The remarkable and troubling thing about the Pharisees is that a group of men who were no doubt interesting companions, good friends, people of sharp intelligence, engaged members of their society, with many genuine excellences and many exemplary traits, nonetheless found themselves fighting against God himself, and they did not know it.

His battle with them was not mainly over their beliefs, what we would now call their theology. Of course Jesus came to perfect and fulfill much in the ancient law, and that meant adjusting to some degree the beliefs of any believing Jew, but the Pharisees were closer to Jesus theologically than almost any other group of Jews of their time. They believed in the resurrection of the dead, and they shared his understanding of the angelic and demonic worlds and his sense of the importance of holiness for the whole people and not just for priests. As it happened, we learn that many Pharisees (like Paul) eventually converted to Christianity, following the example of Nicodemus.

So then, what was the great fault of the Pharisees? It is this: they were darkened in mind.

The importance of conversion of mind for the Christian believer

St. John opens his Gospel with this claim: The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world. Jesus as “light of the world” is an image especially associated with our minds, the highest and noblest part of us. Jesus comes to bring light into a world of darkness, to help us see (understand) what we before could not see. He comes to enlighten the darkened mind.

The Scriptures make it clear that much of what it means to be converted to Christ is to undergo a fundamental change of mind, from a state of darkness and obscurity to one of truth and light. To put off the old nature of sin is to be renewed in the spirit of our minds; to put off conformity to this world means to be transformed by a renewal of our minds.

This can be an elusive truth for us to grasp, since so much of modern religion has been relegated to the category of emotion or tangible spiritual experience. Whatever role emotional experience has to play in the life of a believer, and it is certainly not nothing, it is nowhere close to the heart of the matter. To be converted, for the New Testament, is largely to be enlightened in mind. Faith is the healing of our intellects.

So then, what was the great fault of the Pharisees? It is this: they were darkened in mind.

But what about our wills? Is not the heart of Christianity that we should act rightly, that we become morally upright people? Is not the essence of being a Christian to be a good person? Yes, partly, but in a Christian understanding our minds and our wills are intimately connected: when we see rightly (with our minds), we are oriented to doing what is good (by our wills); if we act wrongly (with our wills), our minds become darkened and we lose proper sight. Hence the great commandment: “Love God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind” (Matthew 12:36). Love God with everything, mind and will and self tied together.

Our age as a Pharisaic age

Back then to the Pharisees: their great fault, expressed in various ways, was that they refused to acknowledge their profound need for God and for his mercy. It is the moral fault of pride of mind, and as a result, their minds were darkened. In the obscurity of that darkness, they were unable to see Jesus, God himself among them. Their pride blinded them to the most important truths. They who claimed to be most enlightened became the fiercest enemies of the one whose name is “Truth.” So Jesus told them: If you were blind you would have no guilt; but because you say “we see,” your guilt remains. Jesus calls the Pharisees blind guides: the blind leading the blind (Matthew 15:14). They were men of darkened mind.

The remarkable and troubling thing about the Pharisees is that a group of men who were no doubt interesting companions, good friends, people of sharp intelligence, engaged members of their society, with many genuine excellences and many exemplary traits, nonetheless found themselves fighting against God himself, and they did not know it. Their blindness and hypocrisy were hidden from themselves. All their good points counted for nothing because they failed in the great test that faces every human. That test is this: will we see and acknowledge our complete dependence on God from moment to moment, he who is the source of all life and thought and truth? Will we recognize our need for his forgiveness and healing, and with a humble mind attempt to align ourselves to him, thereby overcoming our blindness and gaining an illuminated intellect? Or will we find ways, even maybe in the midst of our religious duties, to declare our independence from him, and so remain blind in darkness of mind?

The Pharisee is the intelligent, educated, and morally engaged but intellectually darkened person who has come to rely on himself and has declared, however subtly, independence from God. Who then is the Pharisee of our time? What is the Pharisaical spirit that speaks within us? It is that voice that insists that we too can somehow be independent of God, that we are masters of our own lives, that we have no blindness to overcome but can see with our own light, that we know better than God what is right and wrong (though we would not put it that way), that we know what is the best way for humans to order their lives. We may be a very nice sort of person, with a good sense of humor, helpful to others, engaged in our communities, trying to be morally good according to our own standards, and open to religious ideas. To the degree that we take this independent stance, however, we are acting pridefully like the Pharisees, and our minds will be correspondingly darkened. And like them, we will find ourselves enemies of God without knowing it.

To be converted, for the New Testament, is largely to be enlightened in mind. Faith is the healing of our intellects.

In this light, we can see that we live in a profoundly Pharisaic age. There are many around us, often highly intelligent people, who want to deny any fundamental dependence on God and erect the whole of our society on the basis of plans and ideas and moral principles that have originated in their own darkened minds. Perhaps nowhere is this more in evidence than in the mainstream culture of American colleges and universities: learned, impressive, self-confident, and... darkened in mind and hardened in heart. The dress of the Pharisee today is our tweed jacket, our cap and gown. This cannot have good results: not here, and not in eternity.

Christians at a University

The gravestone of St. John Henry Newman bears the inscription “Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem”: “Out of shadows and images into the Truth.” The motto of the University of Oxford, where Newman spent the first half of his life, is “Dominus Illuminatio Mea”: “The Lord My Light.” The motto of my own alma mater, the Catholic University of America, is “Deus Lux Mea Est”: “God is My Light.” Our motto at the University of Mary is “Lumen Vitae,” taken from the Rule of St. Benedict and the Gospel of St. John: “The Light of Life.” These are fitting mottos for institutions founded by Christians for the training of the mind. For Christians, the starting point for understanding truth, whether of God or of the world, is to pursue enlightenment of mind from its ultimate source: God himself. Our intellects find their proper working capacity in the light given by God. Far from getting in the way of intellectual advance, faith (properly understood) furthers that advance and in fact makes it possible and fruitful. It turns on the lights in what would otherwise remain dark and obscure.

Seeing the importance of overcoming darkness of mind and recognizing how prevalent that darkness is around us – a darkness concerning the most important matters of God and the human and right and wrong, even in the midst of highly sophisticated knowledge – brings the special mission of Christians at a university into greater focus.

- Christians at a university know that the beginning point in any project that involves training the mind – education – is the right-ordering of the mind to the Infinite Mind, God. In the light that God brings, all other matters can then find their proper relation.

- Christians at a university who understand that the human's highest faculties are mind and will and do not divorce one from the other will not make the mistake of thinking that a person's moral behavior has no influence on or relevance to that person's intellectual life.

- Christians at a university know that the training of a human mind is always a spiritual process, and therefore that the life of faith – of proper relation to God who makes thought possible – is a necessary aspect of gaining on truth.

- The hope of Christians at a university is to see all the aspects of the human person brought into proper relation – spiritual, moral, intellectual, physical – "man fully alive," which, in the words of the Church Father Irenaeus, is the "glory of God."

- Christians at a university live their lives in a manner of repentance – constant, joyful repentance – and they love like crazy, so that their hearts become supple and attentive and humble and true. Thereby they become portals of mercy for themselves and all those around them.

In the light of the Lord’s confrontation with the Pharisees, in joyful response to the happy canonization of a great champion this past Sunday, we want to confirm within ourselves certain attitudes and truths. We want to see how near is the temptation to a subtle Pharisaism – a declaration of independence from the source of truth – and not allow that attitude a foothold within ourselves. We want to find ways to love those around us by instantiating and incarnating an integrated Christian life and a mind enlightened by truth – an essential practice of intellectual charity at the heart of the Christian educational mission. We will want to remember the amazing exhortation of St. Paul – that old Pharisee – to the Philippians: "Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things. What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me, do; and the God of peace will be with you" (Philippians 4:8-9).